Into the Fog by Pat David

Black and White photography is a big topic that deserves entire books devoted to the subject. In this article we are going to explore some of the most common methods for converting a color digital image into monochrome in GIMP .

What We are Trying to Achieve

There are a few things you should focus on in regards to preparing your images for a B&W conversion. You want to keep in mind that by removing color information you are effectively left with only tonal data (and composition) to convey your intentions.

©The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

This can be both liberating and confining.

By liberating yourself of color data the focus is entirely on the subjects and composition (this is often one of the primary reasons street photography is associated with B&W). Conversely, the subjects and composition need to be much stronger to carry the result.

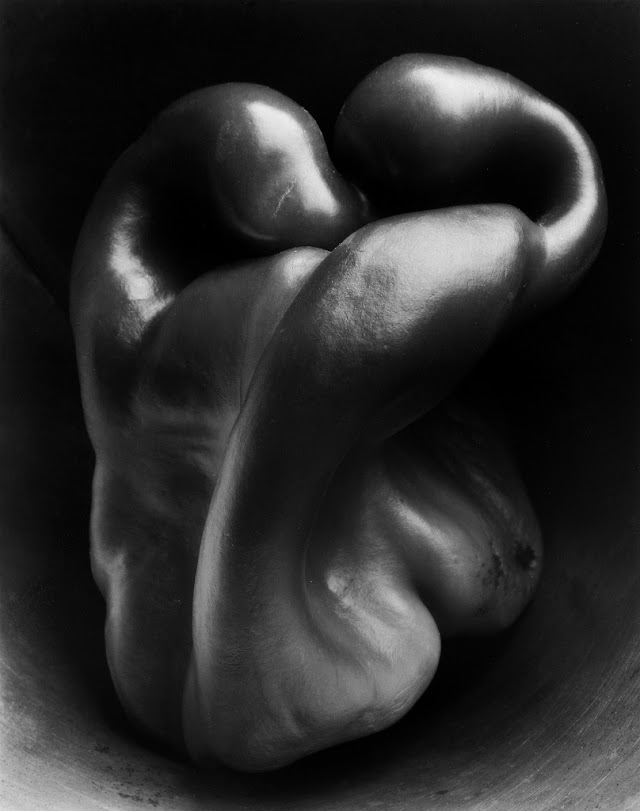

©[Edward Weston, Pepper #30](http://www.edward-weston.com/edward_weston_natural_1.htm)

As an interesting side note, Edward Weston's Pepper #30 is the image that began my personal interest in B&W photography.

Tonality

What I tend to refer to when using this term is the presence and relationship between different values of gray in the image.

This can be subtle with smooth, even differences between values or much more pronounced.

When referred to as the singular “tone”, it is usually referring to a single value of gray in the image.

Contrast

Contrast is the relative difference in tones between parts of an image. High contrast will have a sharper differentiation between tones, while low contrast will have less differences. Often, a straight conversion to grayscale can result in values that are all similar, yielding a tonally “flat” image.

Contrast is often considered in terms of the entire image globally, or in smaller sections locally.

Dynamic Range

Dynamic range is the overall range of values in your image from the darkest to the brightest.

The Approach

The approach we will take here is similar to what I had done in my film days. We’ll attempt to use different methods of grayscale conversion (and possibly blending them) to get to a working image that is as full of tonal detail as possible. Petteri Sulonen refers to this as his “digital negative” – if you want a great look at a digital B&W workflow head over and read his article .

Then, with an image containing as much tonal detail as possible, we will modify it with adjustments of various types to produce a final result that is visually pleasing.

Before heading down that path, it may help to have a closer look at the tools being used. Let’s have a look at how an image gets displayed on your monitor first.

Your Pixels and You

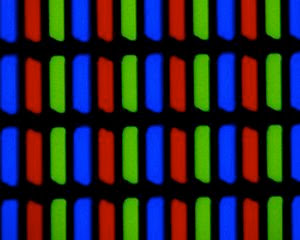

You are working in an RGB world when you stare at your monitors. Every single pixel is composed of 3 sub-pixels of Red, Green, and Blue.

(Image from [wikipedia](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:TN_display_closeup_300X.jpg))

The variations in brightness of each of the sub-pixels will “mix” to produce the colors you finally see. The scales available in an 8-bit display are discrete levels from 0–255 for each color (28 = 256). So if all of the sub-pixel values are 0, the resulting color is black. If they are all 255, you’ll see white. Any other combination will produce some variation of a color.

80, 205, 255 for instance

or 255, 172, 80

But what about 16-bit images? Well - the data is still in the image file to correctly describe the colors at 16bit/channel, but most likely what you'll be seeing on your monitor is an interpolation of the values to an 8-bit/channel colorspace. You should *always* work in the highest bit depth color that you can, and leave any conversions to 8-bit for when you are saving your work to be viewed on a monitor.

The important point to take away from this is to realize that when all three color channels are the same value, you’ll got a grey color. So a middle gray value of 127, 127, 127 would look like this:

127, 127, 127

While this is a little brighter: 220, 220, 220

Very quickly you should realize that a true monochromatic grayscale image can display up to 256 discrete shades of gray going from 0 (pure black) to 255 (pure white), while for 16-bit images, 216 will yield 65,536 different shades. It is this limitation for purely gray 8-bit images that introduces artifacts over smooth gradations (posterization or banding) – and is a good reason to keep your bit depths as high as possible.

Getting to Grey

There are many different paths to get to a grayscale image and almost none of them are equal. They will all produce different images based on their method of conversion, and it will be up to you to decide which ones (or portions of) to keep and build upon to create your final result.

*Conversation in Hayleys* by Pat David (cba)

For this tutorial we are going to try and cover as many different methods as possible. This means we’ll be having a look at:

- Desaturate Command (Lightness, Luminosity, Average)

- Channel Mixer

- Decompose (RGB, LAB)

- Pseudogrey

- Layer Blending Modes

- Film Emulation Presets

- Combining these methods

One of these methods may work fine for you. Or, if you’re like me, it will most likely be a combination of one or more of these methods blended through a combination of layer masking and opacity adjustments.

Desaturate (GIMP)

Perhaps the easiest and most straightforward path to a grayscale image is using the Desaturate command.

It can be invoked from the GIMP

menu:

Colors → Desaturate…

There are three options available from this menu:

Each of these options (Lightness, Luminosity, Average) will generate a grayscale image for you, but the difference lies in the way they interpret the image colors into values of gray.

To illustrate the differences, consider the following two figures. One is a gradient of red, green and blue from black to full saturation. The other are overlapping circles of color in an additive mix.

Let’s investigate each of the desaturation options on these test images.

Lightness

The Lightness method will add the largest value of red, green or blue and the smallest value, then divide the result by 2.

½ × ( MAX(R,G,B) + MIN(r,g,b) )

So, for instance, with an RGB value of 100, 20, 210, the equation would be:

½ × ( **210** + **20** ) = 115

Using the Lightness function on our test images yields the following results:

This means that one channel is actually ignored in creating the final value.

Average

Average will use the numerical average of the RGB values in each pixel.

⅓ × ( R + G + B )

Luminosity

Lightness and Average both evaluate the final value of gray as a purely numerical function without regard to the actual color components. Luminosity on the other hand, utilizes the fact that our eyes will perceive green as lighter than red, and both lighter than blue (relative luminance). This is also why your camera sensor usually has twice as many green detectors as red and blue .

The weighted function describing relative luminance is:

(0.2126 × R) + (0.7152 × G) + (0.0722 × B)

Click to compare to original

No one of these methods is necessarily any better than the other objectively for your own conversions. It really depends on the desired results. However, if you are in doubt about which one to use, Luminosity may be the better option of the three to more closely emulate the brightness levels you will perceive.

Examples

The image below, Joseph N. Langan Park , is an interesting example to see just how much green influences the conversion result using luminosity. Click through each of the different conversion types to them, and pay careful attention to what Luminosity does with the green bushes along the waters edge.

This shot of Whitney shows the effect on skin tones, as well as the change in her shirt color due to the heavy reds present. In just a Lightness conversion, the red shirt becomes relatively flat compared to her skin tones, but becomes darker and more pronounced using Luminosity. Her lips get a bit of a boost in tone in the Luminosity conversion as well.

Channel Mixer

Using Desaturate lets you convert to grayscale based on pre-defined functions for calculating the final value, but what if you wanted even further control? What if you wanted to decide just how much the red channel should influence the final gray value, or to have more control over the ratios and weightings from each of the different channels independently? That’s precisely what the Channel Mixer will allow you to do.

For the examples below I’ll use a different color gradient test map going from blue to blue HSV gradient, with a gradient to black vertically. This represents the entire 8-bit colorspace.

Click to compare: Original Lightness Average Luminosity

Take a quick moment to click through the various desaturation methods already mentioned.

The Channel Mixer can be invoked through:

The dialog will look like this with the test gradient:

The Channel Mixer can be used to modify these channel on a full color image, but we are focusing on grayscale conversion right now. So check the box for Monochrome, which will disable the Output channel option in the dialog (it’s no longer applicable). This will turn your preview into a grayscale image.

Warning: Math Ahead

If you checked the Monochrome option, and left the Red slider at 100, then you’d be seeing a representation of your image with no Green or Blue contribution (ie: you would basically be seeing the Red channel of your image):

What this means is that with Green and Blue set to 0, the values of the Red are directly mapped to the output value for the grayscale image. If you were looking at a pixel with RGB components of 200, 150, 100, then the Value for the pixel in this instance would become 200, 200, 200.

It’s also important to note that the sliders represent a percent contribution to the final value.

That is, if you set the Red and Green channels to 50(%), you would see something like this:

In this case, Red and Green would contribute 50% of their values (with nothing from Blue) to the final pixel gray value. Considering the same pixel example from above, where the RGB components are 200, 150, 100, we would get:

( 200 × 0.5 ) + ( 150 × 0.5 ) + ( 100 × 0 )

( 100 ) + ( 75 ) + ( 0 ) = **175**

So the final grayscale pixel value would be: 175, 175, 175.

Preserve Luminosity

The astute will notice that the sliders actually have a range from -200 to 200. So you may be asking – what happens if two channels contribute more than what is possible to show?

Using the pixel example again, what if both the Red and Green channels were set to contribute 100%?

( 200 × 1.00 ) + ( 150 × 1.00 ) + ( 100 × 0 ) = **350**

While the Channel Mixer will allow us to set these values, we can’t very well set the grayscale pixel value to be 350 (in an 8-bit image). So anything above 255 will simply end up being clipped to 255 (effectively throwing away any tones above 255, bad!).

This means that you have to be careful to make sure that each of the three channel contributions don’t exceed 100 between all of them. 50% Red, 50% Green is ok – but 50% Red, 50% Green, and 50% Blue (150%) will clip your data.

This is where the Preserve Luminosity option comes into play. This option will scale your final values so the effective result will always add up to 100%. The scale factor from the above example would be calculated as:

1⁄( 1.00 + 1.00 + 0 ) = **0.5**

So the value of 350 would be scaled by 0.5, giving the actual final value as 175. If Preserve Luminosity is active, all the values would be scaled by this amount.

This is not to say that Preserve Luminosity is always needed, just stay aware of the possible effects if you don’t use it.

Speaking of Luminosity

Previously we talked about the function used for desaturating according to relative luminance. If you’ll recall, the formula was:

( 0.2126 × R ) + ( 0.7152 × G ) + ( 0.0722 × B )

If you wanted to replicate the same results that Desaturate → Luminosity produces, you can just set the RGB sliders to the same values from that function (21.3, 71.5, 7.2):

If you’re just getting started with the Channel Mixer, this makes a pretty nice starting point to begin experimenting.

Experimenting

A pretty landscape image by Flickr user Cyndi Calhoun serves as a nice test image for experimentation:

by Cyndi Calhoun (cb)

You’ll want to keep in mind the primary RGB influences in different portions of your image as you approach you adjustments. For instance, this image (not coincidentally) happens to have strong Red features (the rocks), Blue features (the sky), and Green features (the trees).

Keep an eye on the individual channels from getting so bright that you lose detail (blowouts), or from crushing the shadows too much. Remember, you want to try to keep as much tonal detail as possible!

So, using the luminosity function as a starting point…

It’s not a bad start at all, but the prominence of the red rocks in the sunlight has been dulled quite a bit. It’s a central feature of the image and should really draw the eye towards it. So the reds could be more pronounced to make the stone pop a little more.

With the Preserve Luminosity option checked, begin bumping the Red channel to taste.

(Click image to compare to base luminosity conversion)

This gives a little more prominence to the red stone.

The Green channel seems ok, but for comparison try lowering it to about half of the Red channel value. Remember – Preserve Luminosity is checked so the final values will scale to give Red values twice the weight as Green.

(Click image to compare to previous step)

This brings up the shadow side of the central rocks a bit as well as adds some definition to the trees and vegetation. Also interesting is the apparent boost to the red rocks as well.

If you’re wondering why the red rocks got brighter as well, consider the math. Previously Red and Green were very near each other in value (around 70), so both colors had approximately equal weight. When Green got its influence cut in half, Red scaled to take a much larger influence, and because there was more red than green the final value will end up higher.

If we look at the RGB values of the red rocks, the values are roughly like this (ignoring Blue for the moment because for this example it’s staying constant): 226, 127.

If both Red and Green have equal influence, the final pixel value will be:

( 226 × 0.5 ) + ( 127 × 0.5 ) = **176.5**

Now if Green is only half as strong as Red, the value will be:

( 226 × 0.5 ) + ( 127 × 0.25 )⁄( 0.5 + 0.25 ) = **193**

The result was divided by the influence amount to scale the way Preserve Luminosity would. The final pixel value will become brighter in this case, which is why the red rocks got brighter with a decrease in the Green channel.

It should go without saying that the Blue channel will have a heavy influence on the sky (and many areas of the image in shadow). To add a little drama to the sky, try removing the Blue channel influence by setting it to 0:

(Click image to compare to previous step)

This will darken the sky up a bit (as well as some shadow areas).

Pay careful attention to what these changes do to the image in closer views. In this case there is a higher amount of banding and noise in the smooth sky if values get pushed too far. So try to approach it with a light hand.

The sliders also allow negative values. This will seriously crush the channel results when applied (and will quickly lead to funky results if you’re not careful). For example, to push the Blue channel even darker in the final result, try setting the Blue channel to -20:

(Click image to compare to previous step)

The sky has become much darker, as have the shadow side of the rocks. There is an overall increase in contrast as well, but at the expense of nasty noise and banding artifacts in the sky.

General Rules of Thumb

The Red channel is well suited for contrast (particularly in the brighter tones).

The Green channel will hold most of the details.

The Blue channel contains grain and (often) a lot of noise.

In skin, the Red channel is very flattering to the final result and you'll often get good results by emphasizing the Red channel in portraits.

On Skin

The Red channel can be very flattering on skin and is a great tool to keep in mind when working on portraits. For instance, below is the color image of Whitney from earlier:

The straight Luminosity conversion is below. Click on the image to compare it to a version where the Red channel is set equal to the Green channel (giving a greater emphasis on the Reds):

(Click to compare Red channel = Green channel)

B&W Film Simulation

Due to the popularity of the Channel Mixer as a straightforward means of conversion with nice control over each of the RGB channel contributions, many people have used it as a basis for building profiles of what they felt was a close emulation to the tonal response of classic black and white films.

Borrowing the table from Petteri Sulonen’s site , these are some common RGB Channel Mixer values to emulate some B&W films. These aren’t exact, of course, but some people may find them useful. Particularly as a starting-off point for further modifications.

| Film | R, G, B |

|---|---|

| Agfa 200X | 18, 41, 41 |

| Agfapan 25 | 25, 39, 36 |

| Agfapan 100 | 21,40,39 |

| Agfapan 400 | 20,41,39 |

| Ilford Delta 100 | 21,42,37 |

| Ilford Delta 400 | 22,42,36 |

| Ilford Delta 400 Pro & 3200 | 31,36,33 |

| Ilford FP4 | 28,41,31 |

| Ilford HP5 | 23,37,40 |

| Ilford Pan F | 33,36,31 |

| Ilford SFX | 36,31,33 |

| Ilford XP2 Super | 21,42,37 |

| Kodak Tmax 100 | 24,37,39 |

| Kodak Tmax 400 | 27,36,37 |

| Kodak Tri-X | 25,35,40 |

There’s a good reason that Channel Mixer is such a popular means for converting an image to grayscale. It’s flexible and allows for a great level of control over the contributions from each channel.

Unfortunately the only way to preview what is happening is in the tiny dialog window. Even when zooming in it can sometimes be frustrating to make fine adjustments to the channel contributions.

Decomposing Colors

Another method of converting the image to grayscale is to decompose the image into its constituent channels. When looking at the Channel Mixer previously, there was an option to set one of the RGB channels to 100 (and leaving the others at 0) that would isolate that specific channel.

If you wanted to isolate each of the RGB channel contributions into its own layer, it would be tedious to do manually. Luckily, GIMP has a built-in command to automatically Decompose the image into different channels:

Colors → Components → Decompose…

Will bring up the Decompose dialog box:

The options available are which Color model to decompose to, and whether to create a new image with the decomposed channels as layers. If Decompose to layers is not checked, there will be a new image for each channel separately (chances are that you’ll want to start out leaving this checked).

The most important option is which Color model to decompose to. Up to now we have mostly been considering RGB, but there are other modes that might be handy as well. Let’s have a look at some of the most useful decomposition modes.

We will be using this image graciously provided by Dimitrios Psychogios :

RGB(A)

This is the Color mode that we’ve been focusing on up to now, and is usually the most helpful in terms of having multiple sources to draw from. This separates out the Red, Green, and Blue Channels into individual layers for you (and Alpha if your image has it).

HSV/HSL

Hue, Saturation, and Value/Lightness is another useful decomposition, though usually only the Value or Lightness is useful for B&W conversion.

The Value in HSV is derived according to a simple formula:

Value, V = MAX( R, G, B )

Which is basically just the largest value of Red, Green, or Blue.

The Lightness in HSL is derived from this formula:

Lightness, L = ( MAX( R, G, B ) + MIN( R, G, B ) )⁄2

Where Lightness is simply determined as the average of the largest and smallest component of RGB.

While Hue and Saturation may seem interesting, it should be obvious that the most useful channels for a grayscale conversion here would likely be Value or Lightness. Overall, Lightness will tend to be a bit brighter than Value.

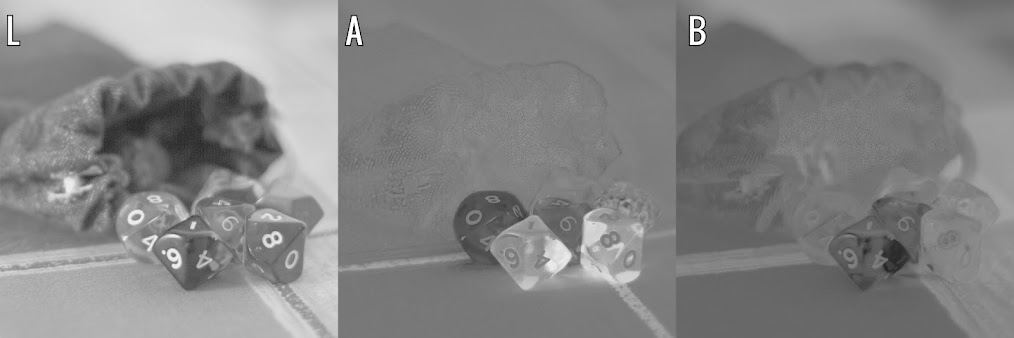

LAB

There is far too much information concerning the LAB colorspace to really go into much detail here. Suffice it to say that the L in LAB is for Lightness, while A and B are for color opponents (A = Green⇔Red, B = Blue⇔Yellow).

Later articles about color toning will show some neat tricks using the LAB colorspace for adjustments.

The LAB colorspace is based on a perceptual model (similar to the relative luminance previously discussed). In fact, the Lightness in LAB is calculated using the cube root of the luminance from that function.

As you can see, the only channel of any use for a B&W conversion is really the Lightness, L channel.

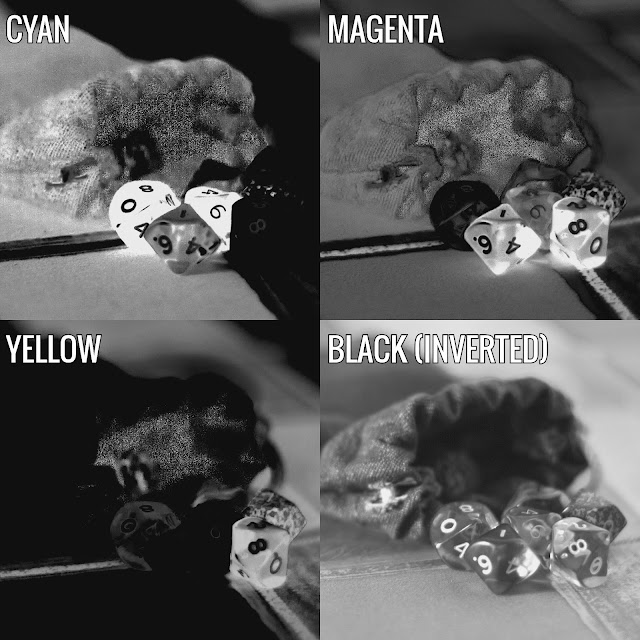

CMY(K)

Cyan, Magenta, Yellow and (Black, K) are often discussed in terms of printing. When doing the decomposition in GIMP, you’ll have to invert the results to make them useful. Once you do, you may notice that they are, in fact, the same as RGB (for CMY decomposition):

CMYK produces a similar result, but adds another channel to control the level of black in the result. Inverting the Black, K channel yields something usable.

YCbCr

Anyone who has done video processing might recognize this colorspace representation, as it often shows up in digital video. YCbCr is a means for encoding the RGB colorspace with three channels: Luma, Y, and two channels of Red (Cr) and Blue (Cb) chroma differences.

Try to use the 256 variants of the ITU recommendations to allow the decomposition to span the full 256 values available (the non-256 versions will pad 16 to the range, only allowing values to go from 16-240).

So What’s the Result?

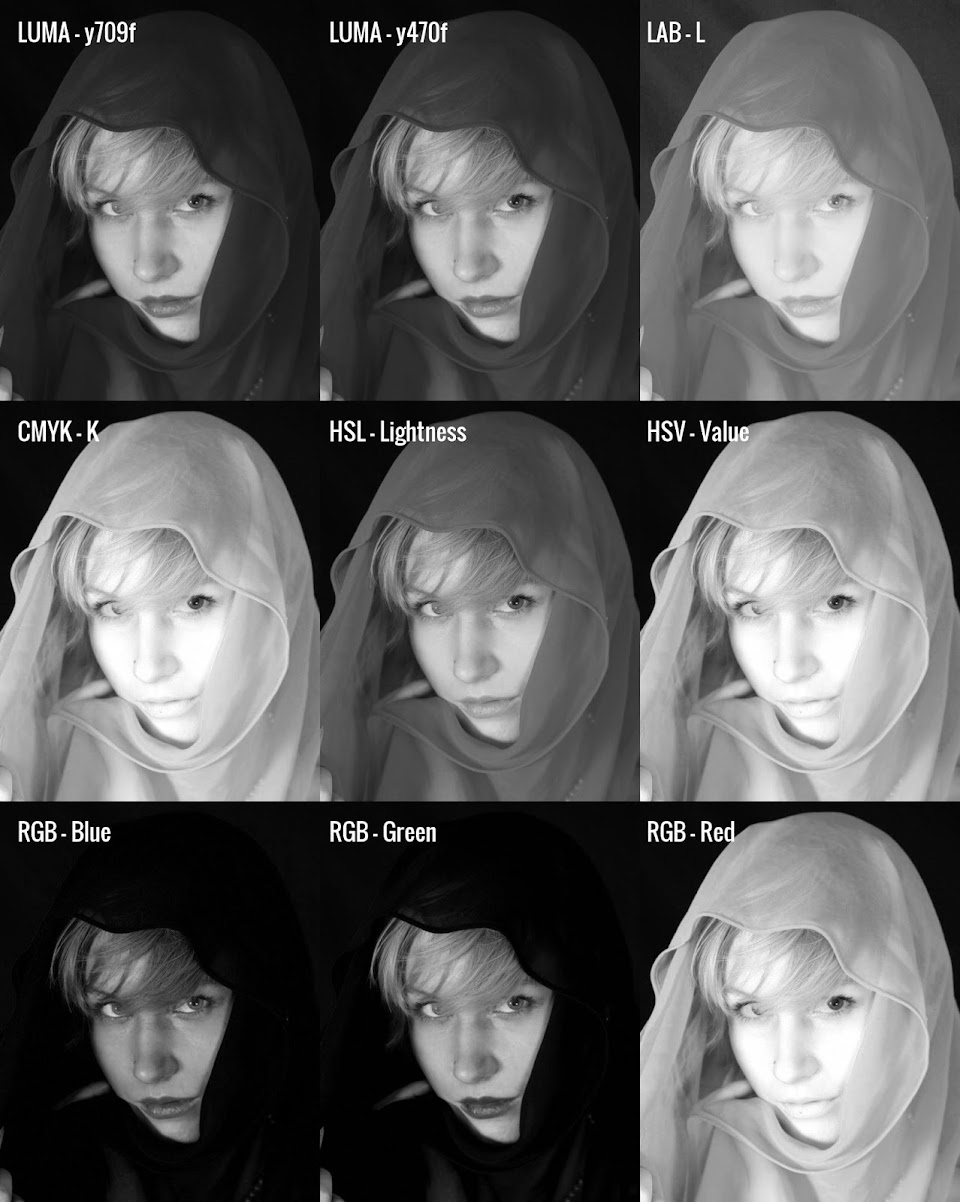

Let’s summarize some of the most useful results from Colors → Components → Decompose for a B&W conversion:

- RGB - All channels

- HSV/HSL - V (Value) and L (Lightness)

- LAB - L

- CMYK - K

- YCbCr - Y (Luma)

This gives a total of 9 different types of color mode conversions that may be useful for generating a B&W image. It helps to visually see all of the options at once to get a better feel for what is going on:

Chances are that one of these conversions might prove useful as a direct B&W conversion.

It helps to notice that the first 4 conversions are all color channels, while the last 5 conversions are brightness values based on different functions for achieving the results (K, Value, Lightness, L, Y (luma)).

The Script

I had previously written some Script-Fu to automate the task of generating these useful channel decompositions (it was tedious choosing each color model manually).

The script will take the active layer in an image, and decompose it to each of the useful color channels listed above, each on its own layer. Once downloaded and placed into your Scripts folder, the command can be found here:

Colors → Color Decompose…

Downloading the Script

The Script-Fu for *Color Decompose* can be downloaded here:

Color Decompose

or downloaded from here:

Color Decompose on Github

Looking Forward

Likely that some parts of some conversions will be useful in some way. I am personally rarely satisfied with any of the straight conversion options on their own, but would like to pick and choose which parts of the image contain the best detail and tones from the different conversion options. The fun is then combining them in such a way so as to produce a final result that is pleasing.

Pseudogrey

Pseudogrey (grey, not gray, per the original author, Rich Franzen ) is a means for increasing the available levels of perceived gray in an image using a bit-stealing technique.

by Pat David (cba)

The basic approach in Pseudogrey is that you can achieve a much higher number of perceived gray values in an image, if you allow some of the pixels to stray just a tiny bit away from pure gray. For instance, if a pixel value in a true gray image was: 180, 180, 180, Pseudogrey may actually make the pixel value something like 180, 181, 180.

That is, the Green value may be just a bit higher. The full post on Pseudogrey goes into much more detail about the algorithm.

The results from using Pseudogrey will follow the same model as for Luminosity desaturation, but will provide a much larger range of tones (1786 possible shades vs 256 in a truly gray image).

There are a couple of ways to convert images to pseudogrey.

There is a Script-Fu available for download:

Downloading the Pseudogrey script

The Script-Fu for *Pseudogrey* can be downloaded here:

Pseudogrey on GIMP Registry

or downloaded from here:

Pseudogrey on Google Drive

Once the file has been downloaded and placed into your Scripts folder, the command can be found under:

Colors → Pseudogrey...

Alternatively, if G’MIC is installed then the command can be found at the Black & white filter:

G'MIC → Black & white → Black & white

At the end of all of the various options in the filter, there is a Pseudo-gray dithering option to apply the algorithm at various levels (higher levels increase the distance from true gray for each pixel).

Pseudogrey can be helpful in areas with slight tonal value changes over a large area, as this is often where banding will become visible in an 8-bit image. While the differences may be slight in many cases, if allowing the tiniest amount of color shifting to creep into the image for an expanded tonal range is ok, then pseudogrey is a great option to have.

GEGL C2G

The Generic Graphics Library (GEGL) is the underlying graphics engine for GIMP. There is one neat function in GEGL specificaly for B&W conversions called Color 2 Grayscale (c2g). It can be found on the Tools menu in GIMP:

Tools → GEGL Operation...

Rolf Steinort covers c2g briefly in episode 84 of Meet the GIMP . Paul Bou also looks at using c2g for B&W conversions in a little more detail, and Joel Cornuz also asks if c2g could be the “ultimate” B&W converter. It may not be worth all the hyperbole, but c2g does do some very interesting things.

The operation considers each pixel relative to its neighbors within a given radius. The value determined is evaluated as a function of perceived luminance weighted against neighboring pixels. The description from GEGL.org is:

Color to grayscale conversion, uses envelopes formed from spatial color differences to perform color-feature preserving grayscale spatial contrast enhancement

In practice, c2g will attempt to scale the values of pixels within its neighborhood (radius) to maximize contrast. What some people like about c2g is that the operation will also introduce a nice range of synthetic grain during the conversion. There are ways to minimize the resulting grain by adjusting settings, though.

Let’s consider this test image:

At first glance, GEGL c2g will likely produce ugly results. The default settings are not conducive to producing a pretty image:

(Click image to compare to original)

The default settings will (usually) produce a nasty halo effect on edges where the radius is not large enough to fully consider transitions. The edges of the buildings/trees against the sky show this particularly. There is also an excessive amount of synthetic graininess to the result.

Tweaking parameters can lead to better results at the cost of processing time. GEGL c2g is not a fast algorithm.

Haloing can be decreased by increasing the radius and graininess can be decreased by increasing the samples or iterations. Iterations seem to have a larger effect on overall noisiness in the result but (again) at the cost of increased processing time.

(Click image to compare to default parameters)

Increasing the radius helped to alleviate some of the halos and will allow the algorithm to spread the contrast over a larger area. The increase in samples and iterations helps to keep the noise down to a more manageable level as well. Refining even further yields slightly better results:

(Click image to compare to original)

At this point the noise is nicely suppressed while the halos have mostly been eliminated. The overall image still has more contrast than the straight luminosity desaturation (click to compare) and the contrast has been weighted for the surrounding pixels as well.

If a luminosity desaturation will choose a pixel value based on the perceived color brightness, c2g will do the same in addition to weighting the result relative to neighboring pixels.

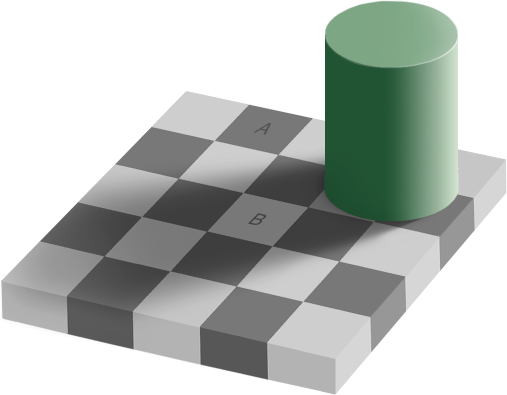

For example, below is an optical illusion showing the effect on perceived luminosity relative to nearby brightness:

Squares A & B are the same exact shade of gray. The reason we perceive B as lighter than A is due to the way our eyes are perceiving nearby colors (and our expectations are strengthened by the checkerboard pattern as well).

The results of running the image through c2g aligns the pixel values closer to what our eyes see:

This operation can be very handy for bringing out micro-contrasts in an image (or increasing global contrast at large radius settings).

Conversion Examples

Finally, a look at a simple workflow for applying these various methods of grayscale conversion to arrive at a final result.

The overall workflow here will be to decompose the image to various grayscale layers. Then to investigate each of the different versions to identify features of interest aesthetically. Finally, combine the different decompositions and mask accordingly to highlight those features or tones.

Pretty Woman

Do a Creative Commons search on Flickr, and it’s very likely that photographer Frank Kovalchek will show up in some fashion. He liberally licenses many photographs under Creative Commons licenses, and we will be using one of his portraits for this first example.

Utilizing the script from earlier to quickly break the image down into multiple layers using different decomposition modes produces a nice array overview to consider:

These various decompositions supply a large amount of possible variations in getting to a finished product. Keep in mind that the goal in this example is to maintain good tonal density as well as imparting a sense of texture and detail.

The Scarf

As good a starting point as any, consider the texture and detail of the scarf. Looking at the various decompositions in the array, the question you should be asking yourself is:

Which of these results produces the best quality/texture in the fabric of the scarf?

Looking at the previews leads to three possible choices: Luma Y709F, Luma Y470F, and HSL - Lightness. Of those let’s go with Luma Y709F. This is very subjective, of course. The important point to take away is the choice being made due to qualities it possesses for a particular purpose.

The main focus of the image will be the models face but you will still want to retain detail and texture in the scarf as well.

The Skin

Looking at the model and her skin there is already fine detail , but could use a bit more emphasis overall. Perhaps get the skin a little bit brighter and in a higher key to offset the dark background and the scarf. It would be nice to smoothen/soften the skin tones as well.

Keeping that in mind, look back at the various decompositions again, this time with an eye towards skin tones and her face. Not surprisingly, the RGB - Red channel looks very pretty (as well as the HSV - Value). It’s fairly common that the red channel will be complimentary on (Caucasian) skin. There is even an old trick to use the red channel as an overlay on a color image to help “enhance” skin tones.

So let’s try that here. Place the RGB - Red channel over the Luma - y709f channel and change the layer blending mode to Overlay.

(Click to compare to base Y709F - Luma)

Visually this appears to have more impact, but the skin may be blown out a little too much. One option to attenuate this would be to lower the opacity on the RGB - Red layer.

Also, note that very often the visual impact may also be due to the higher contrast in the image at this point. Sometimes it's best to stand up and look away from the image for a while before committing to a change...

The problem with adjusting the opacity for the entire layer is that the ratio of levels between the skin and scarf may not be desirable for the final output. Adjusting the opacity might reduce the effect on the skin, but at the same time will reduce the effect on the scarf by an equal amount. What is needed is a way to apply the effect stronger on the scarf or skin separately.

This is exactly what Layer Masks are for!

Masks

At this point a layer mask could be added to the RGB - Red layer, and then painted by hand to modify the intensity by isolating the face and giving a little less opacity to the scarf. It’s a lot of tedious, detailed work.

However, if you look back on the array of decompositions you may notice that channels like RGB - Blue and RGB - Green look pretty good for isolating the face from the scarf already.

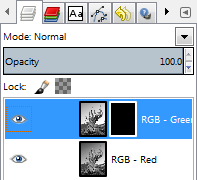

So we are going to use the RGB - Green layer and apply it as a layer mask to the RGB - Red layer.

The Layers palette should look something like this in GIMP now:

Keep in mind, a layer mask will be more transparent the darker the color is in it. The lighter areas will show more of the layer it is applied to. In this case, the lighter areas will allow more of the RGB - Red layer to show, while darker areas will show more of the layer below, Luma - Y709F.

The results at this point with the mask:

(Click to compare without the layer mask)

What this has done is to isolate the models face from the surrounding scarf. You can now modify the opacity of the layer, or adjust the values of the mask using Levels or Curves to adjust the intensity of the result.

Any changes to the RGB - Red layer will now be masked to apply mainly to the models face.

Looking at the results, the scarf has become much more flat in tones, while the models face has brightened up. Considering it, the ratios look backwards a bit. The scarf has flattened out, and the face has brightened a bit too much.

To flip the ratios, simply invert the colors of the layer mask. Select the mask (not the layer itself!), and run:

Colors → Invert

The layers palette will now look like this:

The result on the image so far:

(Click to compare to non-inverted mask)

At this point the results look pretty nice and would make a fine stopping point. The overlay and mask added some nice depth to the scarf fabric while maintaining a nice effect on the skin of the model as well. More work could be done if wanted with adjusting layer mask levels and increasing/decreasing the results on the models skin but this looks good as it is.

A final comparison of the results against a straight color desaturation:

(Click to compare to straight color desaturation)

This path was a little fussier than doing a straight color desaturation but the results are much nicer and is visually more interesting.

Methuselah

Well, this isn’t the actual Methuselah, but it is a similar species of Bristlecone Pine. Once again, image courtesy of Flickr user Frank Kovalchek .

by [Frank Kovalchek](http://www.flickr.com/people/72213316@N00/) on Flickr (cb)

As before, a first look at multiple decomposition modes originally pointed to Luma - Y709F as being a good candidate for the conversion. In this case, the focus would be on the texture of the tree itself. The RGB - Green decomposition also looks quite good to use as a base moving forward.

The primary focus is the gnarled old tree itself and the secondary focus the lighting of the sun across the ground.

While the RGB - Green channel is nice for the tree texture, the sky still appears too bright and the ground could be a bit darker compared to the tree. The sunlight on the upper branches of the tree and topping the brush on the ground gets slightly lost when the sky is so bright comparatively.

Having found a good layer for the tree texture, the other decompositions are examined for something that represents the sky and ground a little better. The RGB - Red channel is a good compromise (the RGB - Blue channel is a little too noisy).

(Click to compare to *RGB - Green*)

RGB - Red looks like a great candidate for the sky and ground, while RGB - Green will do nicely for the tree textures. As before, layer masks can be used to modify the mix of the two layers to arrive at a final result.

Set the RGB - Green channel above the RGB - Red channel on the layer palette, and add a layer mask to the RGB - Green channel layer initialized to Black (full transparency). This lets all of the underlying RGB - Red channel layer show through.

Now with the layer mask active (see the white outline around the layer mask, not the layer itself above), paint with a white color to allow that portion of the RGB - Green channel layer to show through. When painting with white, it will turn the current layer the mask is associated with opaque in those areas – so focus on painting white where the tree is.

Below is a quick mask to illustrate.

The layers at this point will look like this:

The results from applying the mask above to the image:

(Click to compare to straight desaturation)

This could be a good final version, though there is still a bit of noise in the upper-left corner of the sky from the Red channel. This could be fixed by adding another layer mask just for the sky which would allow adjustments to the levels of the sky relative to everything else.

Grain

Following some ideas from the great tutorial by Petteri Sulonen on Digital Black and White , he speaks a bit about grain in B&W images. There are a few different methods of adding synthetic grain to an image but visually the results are less than impressive.

Petteri was kind enough to make available a grain field that he processed himself from scanned film. An easy way to add grain to an image using this grain field is to add it as a layer over the image, set the layer blending mode to Overlay, and adjust opacity to suit.

You can download the grain-field to use here: Petteri Sulonen’s grain field .

Conclusion

There are many ways to get to a monochrome image. The important process to take way from this article is to consider elements of the final image as built up from multiple conversion methods, and controlling/applying them as needed to serve the final result best.

Mix and match the methods presented here to get to the best base for further modifications.